All manufacturers, including Aruba, specify the power (output) at the antenna ports of their APs. RF power can be measured in mW (milliwatts) or dBm (decibels per milliwatt). 0 dBm equals 1 mW. If the dBm value is negative, the milliwatts are rounded down to a decimal point.

in other words, mW (milliwatt) represents data linearly, while dBm represents data in logarithmic form.It is expressed as .

RF power affects the size of an AP's coverage area, the distance the signal can travel, signal quality, and data rate.

mW (milliwatts) vs dBm

There are several concepts related to RF power, signal strength and measurement.

As explained above, you can measure the output power of the transmitter and the strength of the received signal in units of mW or dBm.

This is a unit of measurement for the same data, similar to measuring the same body weight in kg (kilograms) or lb (pounds).

Because RF power is a logarithmic function, it doesn't behave linearly. For example, if the signal strength at a distance of 1 meter from the AP is X, the signal strength at a distance of 2 meters will be 1/4, not halved.

Although milliwatts are sometimes used to measure RF power, the more common unit is dBm.

When a client's signal strength at close range is 0.00001 mW and at a far distance the signal strength is 0.0000001 mW, these numerical concepts are too difficult to judge.

So, as an alternative, we'll measure in dBm instead of mW. This might seem a bit strange at first, but it's much easier to use.

When an RF signal is transmitted Free Space Path Loss (loss due to distance between transmitter and receiver)The amount of signal received is much less than the amount actually transmitted. When working with mW (milliwatts), working with values ranging from 100 mW to 0.0000247 mW or even less can be very complex and confusing.

For this reason, we use the dBm unit to better understand RF communications. A signal transmitted at 100 mW is equivalent to 20 dBm. A signal received at 0.0000247 mW is equivalent to -46 dBm. 0 dBm is equivalent to 1 mW.

Measuring RF power in mW is done in logarithmic form, which quickly becomes a small number and difficult to manage. Therefore, dBm is a measure of radio energy, and the number is easier to use and more appropriate.

Correlation between mW and dBm

When dealing with wireless issues, including Wi-Fi, we often encounter dBm-related issues. In particular, dBm values are often used for troubleshooting when checking wireless quality or coverage.

Therefore, it is important to understand the following rules when dealing with mW and dBm:.

An increase of 3 dBm is equivalent to doubling the power. An increase of 10 dBm is equivalent to a tenfold increase in power. This rule also applies to decreases.

Let's understand it with an example. Each 3dBm decrease means that the power decreases by 50%.

0dBm = 1mWTherefore, 20dBm is 10x x 10x = 100mW of power.

Typically, when setting the AP transmission power, there are settings of 20dBm or 17dBm. 20dBm = 100mWBecause of this 17dbmIf so, then 50% of 100mW, because it is reduced by 3dBm, 50mWYou can see that.

As another example, Transmit at 14dBmLet's say we have configured the AP to do so.

Omnidirectional antennas radiate radio signals in a hemispherical pattern, giving them a large, balloon-like shape. 25mW of poweris evenly distributed. The client terminal receives only a very small portion of the AP power that reaches the antenna.

The dBm law is very applicable here. Terminals very close to the AP -50dBmIt will display the signal strength of the 0.00001mWThis is actually a very good signal strength. -60dBm is still a very good signal condition. –70dBm is 0.0000001mWWell, it's not great, but it's still usable.

You can see that as the 10dBm decreases, the transmission power drops to 1/10.

Typically, -67dBm is targeted for field testing of AP coverage, etc.

First, set the power of the test AP to 50%. Then, using a field-testing software (such as RF Plan), measure the -67dBm signal of the AP and draw an outline on the floor plan. Then, place the APs so that each -67dBm circle overlaps another AP by 15 to 20%.

Another key value is -95 dBm to -100 dBm, which is the “Noise Floor” and represents typical background noise in most environments.

Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR)

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a measure of the power of a wireless local area network (WLAN) signal compared to the background noise in the RF environment. SNR is essential for assessing signal quality. To identify a WLAN signal, the receiver must receive it at a level higher than the surrounding RF noise level.

Many wireless client terminals require a 10-20 dB difference between the wireless signal and noise level.

EIRP (Effective Radiated Power)

Depending on the book you read, EIRP is called Effective Isotropic Radiated Power or Equivalent Isotropic Radiated Power. In both cases, EIRP refers to the maximum output power of an antenna system.

Here, the total RF output is the sum or subtraction of the RF transmitter, amplifier, attenuator, and antenna gain.

Each country sets legal limits on maximum EIRP. Exceeding this threshold is illegal. This is generally not a concern for Aruba APs with built-in antennas, as they are often installed indoors. Manufacturers have already confirmed that these products legally generate the maximum power.

However, EIRP is important when deploying outdoors or performing long-range bridge shots, especially using high-gain antennas.

Let's assume that the transmission power of the AP is set to 20dBm or 100mW, as shown in the figure above.

When connecting a cable to the AP using the appropriate connector, the signal experiences a loss of approximately -3 dBm, decreasing to 17 dBm by the time it reaches the antenna. However, the antenna has a gain of 10 dBi, providing a total EIRP of 27 dBi.

In the United States, the maximum limit is 36dBm, but each country has different limits.

In Korea, there are regulations regarding the maximum absolute gain for external antennas.

Wireless LAN (WLAN) mobility

The Basic Service Set (BSS) includes the AP and all clients within the AP's coverage area. A wireless MAC address, known as the BSSID, identifies this BSS. All WLAN clients associated with the AP are considered part of the BSS.

An Extended Service Set (ESS) includes all clients connected to the same logical network name. The SSID or ESSID is case-sensitive and identifies the wireless network (WLAN) to the client. The AP broadcasts both the BSSID and SSID over the air in beacons or probe frames.

The SSID consists of a 48-bit MAC address, which is derived from the physical MAC address of the AP's wireless radio and becomes the BSSID.

Let's say an AP has a MAC address of aa:aa:aa:aa:aa:a0 on its 2.4Ghz radio and broadcasts an (E)SSID called "guest." That SSID could be assigned a BSSID like aa:aa:aa:aa:a1. Then, if you create a second (E)SSID on the same radio, it could be assigned a BSSID like aa:aa:aa:aa:a3.

You can do the same thing with other APs. Of course, their 2.4Ghz radios have different MAC addresses, such as bb:bb:bb:bb:bb:b0. Therefore, the first (E)SSID you create will be assigned the BSSID bb:bb:bb:bb:bb:b1, and the second (E)SSID will be assigned bb:bb:bb:bb:bb:b3.

So why do we need multiple SSIDs on our wireless network?

There are several reasons for this.

- Different authentication types (e.g., guests or contractors vs. employees)

– Captive Portal-style web login

– 802.1x login to Windows Active Directory - Separated by wireless radio type

– 2.4Ghz

– 5Ghz

This way, SSIDs are separated based on authentication or radio type.

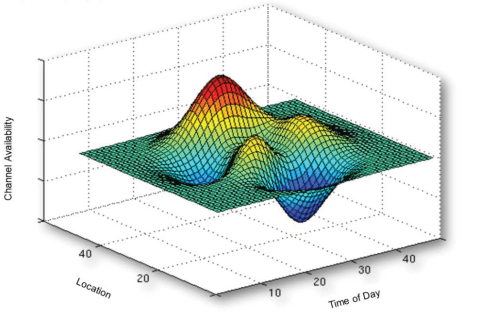

Mobility of wireless terminals – Roaming

Wirelessly connected devices are mobile. Most are used on the move rather than stationary in one location. Our smartphones, tablets, and laptops all allow us to stream videos or work on the go.

When a terminal moves like this, it disconnects from the access point it was previously connected to and attempts to connect to a different one. While the client terminal itself connects to the same SSID, each radio has a different MAC address and unique BSSID, so the BSSID it connects to changes.

802.11 wireless clients moving from one access point to another RoamingIt is called.

When roaming this way, you change your connection point to the network while maintaining the same logical WLAN and SSID.

The controller supports this roaming while maintaining client authentication, session state information, and firewall sessions. This ensures seamless roaming at the application level.

This time, we learned very simply about wireless signal output and dBm, which is used to calculate it.

And we also looked at how wireless clients move from one AP to another by this signal output.

Now that we've covered the basic concepts of wireless Wi-Fi, let's dive into the Aruba wireless portfolio and architecture.